First Came IPv4, Then IPv6. What Happened to IPv5?

IPv4 and IPv6 are the only two versions of the Internet Protocol in use. Discover what happened to IPv5 and whether or not the current versions of the Internet Protocol could be replaced by new versions.

Have you ever wondered what happened to IPv5? If you have, you are not alone. Anyone researching the Internet Protocol and its different versions comes across this question sooner or later.

Today, the dominant version of the Internet Protocol – the main protocol that defines routing and addressing rules – is IP version 4, or IPv4. The infrastructure of this version supports IP addresses that internet users are most commonly familiar with.

An IPv4 address is 32-bits long, and it is expressed in numbers separated by dots. This is the IP address that you can discover when you type “what is my IP address” into the search engine.

The funny thing is that we have run out of IPv4 addresses, and the logical thing to do would be to transition to the next version of the Internet Protocol. As you might know already, that is IPv6 – Internet Protocol version 6.

Why did we jump from IPv4 to IPv6? Why was IP version 4 the first version to be deployed? What comes after IPv6? Continue reading to find answers to all these fascinating questions.

What is Internet Protocol and why do different versions exist?

The Internet Protocol is a communications protocol that enables routing and addressing data packets. These packets contain the information we send or receive to communicate over the internet.

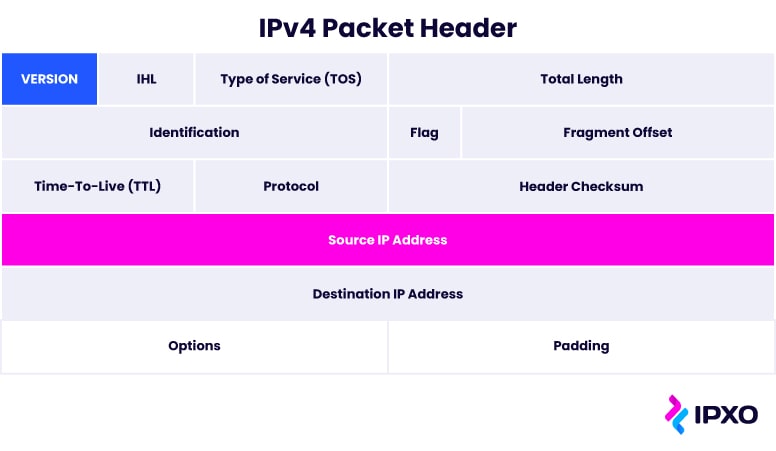

Every data packet has a packet header. This is where the origin and destination IP addresses are located to ensure that information travels to the right recipient. The packet header also includes the version number of the Internet Protocol, which the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) assigns.

Internet Protocol version numbers

| Number | Known as | Version status |

| 0-1 | Reserved | |

| 2-3 | Unassigned | |

| 4 | IPv4 | Internet Protocol v4 |

| 5 | ST | Reserved (Historic) |

| 6 | IPv6 | Internet Protocol v6 |

| 7 | Reserved (Historic) | |

| 8 | Reserved (Historic) | |

| 9 | Reserved (Historic) | |

| 10-14 | Unassigned | |

| 15 | Reserved |

IPv4 is the first version of the Internet Protocol to be deployed

IPv4 emerged in 1981 with a Request for Comments note number 791 – RFC 791. This was the first version of the IP that was available for public use. And what happened with the first three versions?

Before the birth of the Internet Protocol, as we know it today, network architects were working on the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). TCPv1, TCPv2 and TCPv3 were completely experimental, and regular internet users never used them.

IPv4 was the first version deployed, but it was never created as the ultimate version of the Internet Protocol that would never need replacing. In fact, it became evident quite soon that IPv4 would require an alternative. Why? To put it simply, there were not enough IPv4 addresses.

There are precisely 4,294,967,296 IPv4 addresses, and while that might seem like a lot, IP addresses are unique device identifiers. Of course, such technologies as Network Address Translation can help use IP resources more sustainably, but the fact is that there aren’t enough IPv4s to support all internet-connected devices today.

IPv6 emerged to solve the shortcomings of IPv4

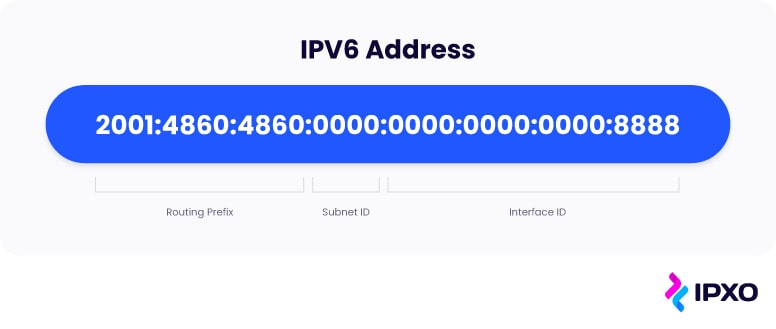

The impending shortage of IPv4 resources is one of the reasons why IPv6 came around in 1995 with RFC 1883. IPv6 addresses are 64-bits long, which means there are 340 undecillion unique addresses. In theory, we will not see a shortage of IPv6 addresses.

Besides the fact that the IPv6 address space is bigger, the sixth version is also superior in terms of security and mobility. If we were to compare IPv4 vs. IPv6, the winner is clear. Nonetheless, we are still pretty much fully reliant on IPv4.

The reason why we moved from IPv4 to IPv6 is clear – we needed more resources. But why did we skip IPv5?

What is IPv5 and why didn’t it work out?

Here’s the kicker – IPv5 never actually existed. Although there is an IP version with 5 assigned as its number, only two versions of the protocol are actually recognized by their numbers: IPv4 and IPv6. In fact, what we refer to as IPv5 is officially known as the Internet Stream Protocol (ST).

James W. Forgie first proposed the Internet Stream Protocol in 1979 with the Internet Experiment Note number 119 – IEN 119. In 1990, the Network Working Group revised the note with RFC 1190.

The Group introduced Internet Stream Protocol Version 2 (ST2) “based on results from experiments with the original version, and subsequent requests, discussion, and suggestions for improvements.”

So, what is the Internet Stream Protocol? In simple terms, it should have been a transport protocol that transmitted human speech across the networks. The second version, ST2, was specifically designed to transmit video calls. Neither ST nor ST2 were ever deployed for public use, as both were experimental protocols.

Basically, ST/ST2 was not built as an alternative to IPv4, and it was not a predecessor to IPv6 either. However, to distinguish ST and IPv4 packet headers, IP Version 5 was included in the ST packet header. As a result of that, the creators of the next deployable Internet Protocol version decided to eliminate the potential element of confusion and jump ahead to IPv6.

In short, there was no IPv5 release date that failed for some dramatic reason. We don’t really need to compare IPv5 and IPv6. And you do not need to google how to upgrade IPv5. IPv5 simply did not exist.

What happened to IPv5 after IPv4?

You now know that the so-called IPv5 never became an official protocol. But why is that? We must look back at IPv4 to answer this question.

It is no secret that the biggest problem with IPv4 is that it can only provide 4.29 billion IP addresses due to its 32-bit addressing capacity. Well, IPv5 offered the same addressing capacity.

By the time the Internet Stream Protocol 2 came to be, the imminent exhaustion of IPv4 was already clear. Therefore, introducing yet another protocol that could not support the global internet infrastructure for long would have made little to no sense.

Well, do we need that many IP addresses? There are over 5 billion internet users who are likely to operate over 27 billion IoT devices by 2025. The number of internet users grows daily, and internet-connected devices are becoming more and more prevalent too. IoT (Internet of Things) is booming and the IoT industry needs more IPs to support the infrastructure. However, it is not the only industry that needs that.

So, doesn’t that mean that we should speed up IPv6 adoption? If only it were that simple.

Are we sticking with IPv4, or should we move on to IPv6?

IPv4 addresses were exhausted in 2011 – over a decade ago – yet we continue using them every single day. How is that possible? First, IP addresses do not expire. They can be used indefinitely. They can even be reused. For example, internet service providers (ISP) use dynamic IP addresses, which customers can use temporarily. Second, not all resources are utilized efficiently.

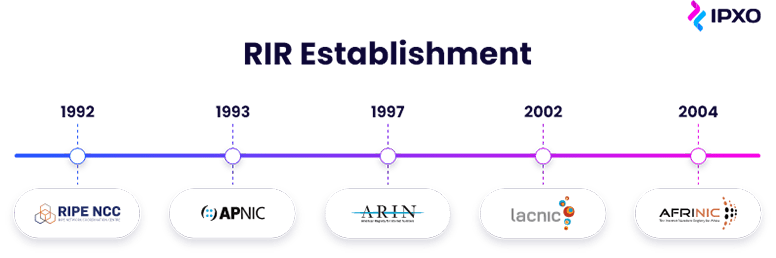

IANA became responsible for the allocation of IP addresses – as well as autonomous system numbers – in 1988. First, the organization assigned internet numbers directly. Later on, this responsibility fell on the shoulders of Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). Today, five RIRs exist in total, and they are the ones allocating the remaining IPs to ISPs and Local Internet Registries (LIRs) who, in turn, allocate the resources to individual internet users.

In the 80s and early 90s, anyone could get free IPv4 allocations. As a result of poor resource management, some companies received more than they could ever need. Even today, these companies own resources they are not using.

When will IPv6 take over?

Once IANA allocated the last blocks of IPs from its pool, RIRs started introducing stricter rules on who could receive IPv4 allocations. Unfortunately, by that point, it was already too late to stop the global exhaustion of the resource.

IPv6 should have offered a solution to the scarcity of IPv4 addresses, but decades after its introduction, it is still not the dominant version of the IP. Even back in 2013, Cloudflare speculated that, in the best-case scenario, IPv6 would take off in early 2020. However, they also introduced a more pessimistic scenario – May 2148. Clearly, the optimistic prognosis did not come true.

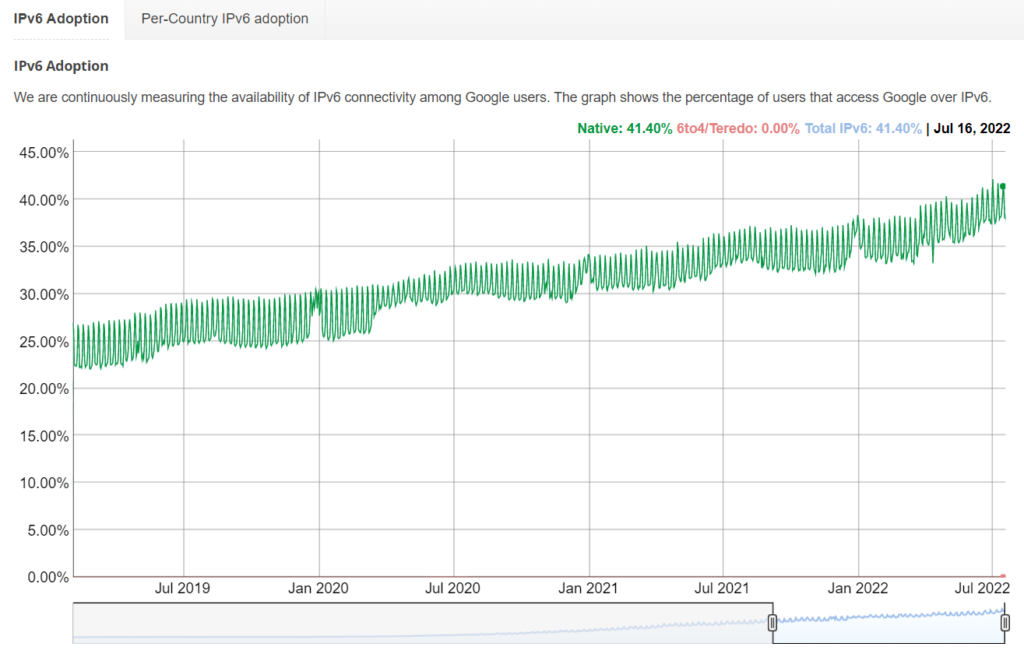

Today, Google records just over 40% IPv6 adoption at peak times. This is nowhere near the number that the developers of IPv6 expected back in 1995.

If IPv6 offers more resources and is better overall, why haven’t we adopted IPv6 already? High adoption costs and lack of training for network administrators are some of the main reasons that hinder wider IPv6 adoption. The bottom line is that there is little motivation from technology developers and network admins to adapt to the new version of the Internet Protocol.

At this point, it is clear that IPv6 will not replace IPv4 any time soon. In the future, both are likely to coexist. And what do we do now? There are two main options: buy/sell or lease.

Buying, selling and leasing IPv4

Now that it is basically impossible to get fresh new IPs, companies that need IP addresses must find new ways to acquire them. Of course, joining a waiting list and waiting for the RIR to recover unused IPs is still an option. In this case, the company needs to justify the request for IPs and then sit and wait.

For example, at the time of publication, the first in line on the ARIN Waiting List had requested a /22 allocation in January 2022. There were 368 requests in total, and the next distribution date was October 3, 2022.

Not everyone can wait for IPv4 resources. In that case, companies often look into buying IPs. It goes without saying that IPs are not cheap these days. IPv4 addresses are a highly desirable commodity, and IPv4 prices have been skyrocketing lately.

Luckily, companies don’t need to surrender all of their money to buy IP resources or give up their ambitions to grow. Instead, they can lease the IPv4s they require at low upfront costs.

IPXO, the world’s first fully automated IP management and lease platform, already offers 2+ million IPv4 addresses from trustworthy IP holders. The platform is expanding rapidly, and the number of IPs available for lease is growing as well. At an average price of $0.48 per IP per month (on July 21, 2022), scaling is completely manageable. Even better, it is quick, easy, accessible and sustainable.

The best part is that there are still plenty of resources that we can put up for lease. According to Geoff Huston, around 800 million IPv4 addresses (49 /8 blocks) remain unused. If we can bring these assets back into the market, companies around the world can not only grow but also thrive. And companies holding unused IP addresses can unlock a recurring revenue stream.

What comes after IPv6?

To recap, TCPv1, TCPv2 and TCPv3 created throughout the 70s were experiments that gave way for IPv4 in the early 80s. Then came the Internet Stream Protocol (ST) and its more advanced version – Internet Stream Protocol 2 (ST2). Although some referred to ST/ST2 as IPv5 because it included Internet Protocol version number 5 in its data packet header, it was an experimental protocol that was never introduced to the public. Ultimately, IPv5 addresses were never a thing.

To make sure that no one confused ST with the latest version of the Internet Protocol, the creators decided to name it IPv6. However, this is not the last version that was proposed to replace IPv4.

IP versions numbered 7, 8 and 9 were also proposed, but, eventually, their statuses were changed to Reserved (Historic). Interesting to note is that IPv9 was an April Fool’s joke by IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force).

Does that mean that IPv10 is the next version of the Internet Protocol to replace IPv6? According to the IPv10 draft introduced in 2017, the new protocol would enable smooth communication between IPv4 and IPv6, and so even if it was deployed, it wouldn’t be a replacement.

How to use the resources we already have

Although free IPv4 addresses have been exhausted, and this version of the Internet Protocol has been around for four decades now, it doesn’t look like we are going to abandon it any time soon. Yes, IPv6 is superior in many ways, but technology developers and network administrators are not quick to adopt it, to put it lightly. In fact, some industry experts do not expect full IPv6 adoption for many years.

Although new versions of the Internet Protocol are always in the works, as history shows, the majority of them do not leave experimental stages. Officially, there are no IP versions that could replace IPv4 and IPv6. And now that you know what happened to IPv5, hopefully, you understand why we never had IPv5 addresses and why IPv4, IPv5 and IPv6 were not introduced in sequence.

Today, IPv4 is the backbone of the internet, and we must preserve this resource as best as we can. For IPXO, the priority is to bring out unused IPs and show companies how easy it is to monetize this asset. For companies that cannot grow due to the shortage of IPv4 addresses, the ability to lease at reasonable prices could determine the success of their operations.

The sustainable internet is here, and it is fueled by good old IPv4 addresses that some have no use for while others are desperate to get. As long as we can balance the demand and supply, we can get by without IPv5, IPv6 or any other iteration of the Internet Protocol for a long time.

About the author

Table of contents

What is Internet Protocol and why do different versions exist?

IPv4 is the first version of the Internet Protocol to be deployed

IPv6 emerged to solve the shortcomings of IPv4

What is IPv5 and why didn’t it work out?

What happened to IPv5 after IPv4?

Are we sticking with IPv4, or should we move on to IPv6?

When will IPv6 take over?

Buying, selling and leasing IPv4

What comes after IPv6?

How to use the resources we already have

Related reading

Open Internet and IP Address Management

Embrace the Open Internet's principles and navigate the evolving landscape of IP address management. Discover how we're adapting to new realities at IPXO, empowering you with access to IP…

Read more

The Evolution of Route Origin Authorization: Insights from IPXO’s Half-Year Journey

Discover the transformative power of Route Origin Authorization and fortify your network's security and efficiency with valuable insights from IPXO's mid-2023 journey.

Read more

What Is More Energy-Efficient: IPv4 or IPv6?

The transition to IPv6 holds the potential to reduce global energy consumption and foster a sustainable future in networking. However, the slow adoption rates of IPv6 have prompted alternative…

Read moreSubscribe to the IPXO email and don’t miss any news!